Scientist on the Trail: Travel Letters of a. F. Bandelier 1880-1881

Afterwards Lewis's preliminary sketch, many have contributed to the process of illustrating the Keen Fall of the Missouri—Lewis's sublimely k fall.

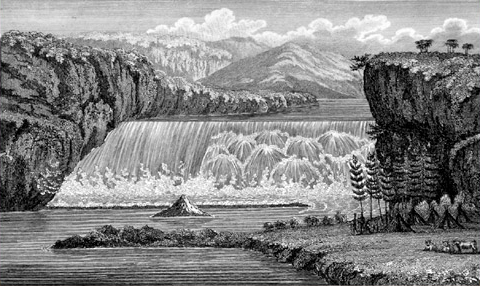

Main Cascade of the Missouri

Courtesy of Watzek Library, Lewis & Clark College, Portland, Oregon

Engraved from a drawing by John James Barralet (1807)

Lewis's Preliminary Sketch

After Lewis finished describing the Great Falls, he lamented that his words failed to do justice to the scene. He "wished for the pencil of Salvator Rosa or the pen of a Thompson," in lodge that he "might exist enabled to give to the aware world some only idea of this truly magnifficent and sublimely grand object; [1] Throughout the 18th century and well into the 19th the thousand and the sublime were qualities one dreamed of encountering somewhere in nature's scenery, sometime. Information technology would be a acme experience. … Proceed reading

As the British critic Lord Henry Habitation Kames had written, there was "a real, though dainty, stardom between these ii feelings"—between grandeur and sublimity. The distinction was a matter of literary expression, of mastery of style. To illustrate, he compared a passage from the Iliad as a simile for grandeur with ane from Milton for sublimity. Meriwether Lewis recognized them both, and he knew when he was in their presence. The right side of the Dandy Fall was grand; the left was sublime. [2] Kames, Elements of Criticism (Dublin: Charles Ingham, 1772), 128-129; Google Books. . . . but this was fruitless and vain." So, he concluded:

I therefore with the assistance of my pen only indeavoured to trace some of the stronger features of this seen past the assistance of which and my recollection aided by some able pencil I hope notwithstanding to give to the earth some faint thought of an object which at this moment fills me with such pleasure and astonishment, and which of it's kind I will venture to ascert is second to but one in the known world.

His phrase "second to only one in the known world" could but have been a reference to Niagara Falls, betwixt Lakes Erie and Ontario, nearly Buffalo, New York. [3] For comparison, run into Niagara Falls by Fr. Louis Hennepin and Niagara Falls past Karl Bodmer (1809–1893).

On xvi July 1806, Lewis and his three companions, en route from White Carry Islands to explore the upper Marias River, paused at the "handsom fall"—now Rainbow Falls. That night they camped under the "shelving rock" in the "little wood" below the "grand falls" . . . after evicting ii bears from the premises. The falls, Lewis noted as he sketched the scene, "accept abated much of their grandure since I beginning arrived at them in June 1805, the water being much lower at prese[n]t than it was at that moment, however they are still a sublimely chiliad object." He arose early the next forenoon and made a second drawing of the falls before proceeding on to the Marias River.

Barralet's 'Pencil'

Upon his return to Philadelphia in 1807, Lewis hired an "able pencil," John James Barralet for 40 dollars to make "two Drawings water falls." [4] Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1873-1854 (2nd ed., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 2:463n. Barralet (c. 1747-1815) emigrated to … Continue reading Lewis probably showed the creative person his ain sketches of the "stronger features" of the yard falls and did his best to refine the details verbally, striving to recapture the essence of the "sublime" he had recognized in the scene. [5] Noah Webster, in his Compendious Lexicon of the English Language (1806), defined "sublime" simply equally "lofty or grand style." An engaging essay on the history of this … Proceed reading

On 26 Jan 1810, Clark wrote to William D. Meriwether that he was in Philadelphia "serching for the Materials left in this City by the late Govr. Lewis, reletive to our discoveries on the Western Tour." Amongst his findings he mentioned "imperfect drawings & made of the falls of the Missouri, & Columbia." [6] Jackson, 2:490. It is non articulate whether he had in mind Barralet'south drawings, or Lewis's and maybe his ain sketches. If the former, that might explain why Barralet's illustrations were non included in the 1814 Biddle-Allen edition of the captains' journals. Indeed, compared with Salvator Rosa's delineation of a waterfall, or G. Beck's 1802 painting of the Great Falls of the Potomac River, Barralet's endeavour appears fibroid and graceless. In whatsoever example, none of the original copies of any of the drawings take notwithstanding been found. [7] An undated note of Clark'due south, to which Jackson referred in connection with a letter from Nicholas Biddle to Clark dated seven July 1810, reads: "The ii Drawings of the Falls of the Columbia … Continue reading

Barralet'southward picture, "Primary Cascade of the Missouri," appeared only in the Irish reprint of the History of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clarke published in Dublin in 1817. [8] Stephen Dow Beckham, et al, The Literature of the Lewis and Clark Expedition: A Bibliography and Essays (Portland: Lewis & Clark College, 2003), 156. Since Bradford and Inskeep underwrote that press, it may be that the American publisher urged the inclusion of the Irish artist's work.

Sohon's 1853 Lithograph

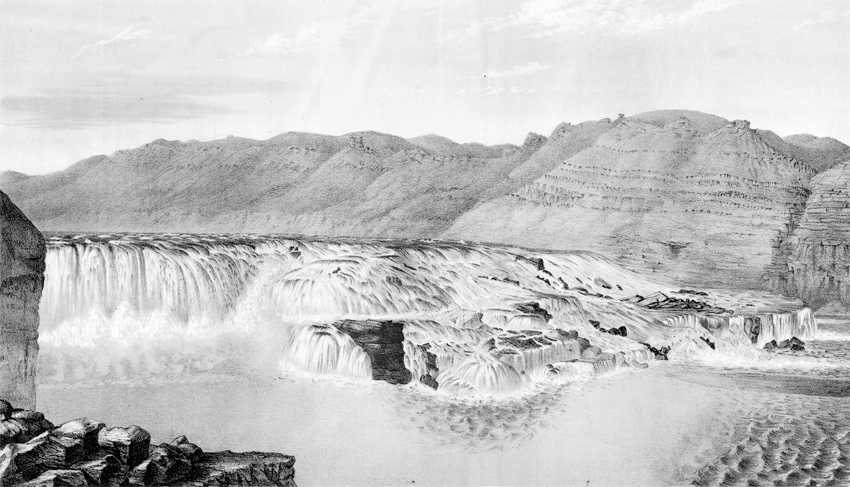

Peachy Falls of the Missouri

by Gustavus Sohon (1853) [9] Isaac. I. Stevens (1818-1852), Narrative and concluding reports of explorations and surveys to ascertain the most practicable and economical route for a railroad from the Mississippi river to the Pacific … Keep reading

Many of the figures whose names we summon to flesh out the story of the Lewis and Clark trek may seem to take lived for no other purpose, when in fact their ain stories are varied and interesting. Such a man was Gustavus Sohon (1825–1903). Born in the urban center of Tilsit, in today's Lithuania, near the Baltic Sea, Sohon emigrated to the U.South. in 1842, at the age of seventeen, and began working as a bookbinder. He was also a talented artist, every bit well equally a gifted linguist. In 1852, having easily learning several Indian languages, he began a five-year enlistment in the U.S. Regular army as an artist and interpreter on several regime-sponsored expeditions, most notably the one led past Isaac Stevens in 1853-1855 to locate potential railroad routes to the Pacific Coast. In 1862, he was called to Washington, D.C. to assist in the completion of the official study of the Stevens survey. After war machine service he operated a photographic studio in San Francisco for two years (1863-1865), then returned due east to carry on a show business in Washington, D.C. Meanwhile, Sohon's hand-tinted lithographs of Western scenes remained an of import ground for pop perceptions of the Far West.

Mathews' Infrequent Perspective

Bang-up Falls of the Missouri

Lithograph by A. E. Mathews [10] A. E. Mathews (1831-1874), Pencil Sketches of Montana (New York: published by the author,1868), Plate XXIV.

Special Collections, Mansfield Library, The University of Montana, Missoula

The sketch, Mathews wrote, "was made from the left-hand bank, which has rarely been visited by white men. The creative person crossed the river beneath the falls on a small log raft, at eminent peril of being dashed past the furious electric current confronting some of the many sharp rocks with which it is filled. On either side of the Missouri there are long Buffalo trails, worn in many places into gullies, leading from the praries at the foot of the afar mountains to the river. Since the all-encompassing travel on the Helena and Fort Benton road, Buffaloes are becoming scarce in this part of Montana." [11] The route Mathews referred to was part of the Mullan Road, a federal project begun in 1859 and completed in 1862 under the direction of Lieutenant John Mullan, of the U.Southward. Army's Corps of … Go on reading

Alfred Edward Mathews (1831-1874) emigrated to the U.S. from England to go an itinerant bookseller and artist. After serving in the Ceremonious War he headed due west, producing some of the primeval views of Texas (1861), Colorado (1866 and 1870), and Gems of Rocky Mountain Scenery: Containing Views Along and Near the Union Pacific Railroad (1869).

The technology basic to the science and art of photography evolved during the 18th and early nineteenth centuries. In 1816 a French scientist combined the camera obscura with photosensitive paper, and afterwards ten more years of experimentation finally produced a permanent epitome. In 1837 Louis Daguerre successfully demonstrated his invention, past which a copper canvas coated with silver iodide was "exposed," and so "adult" with warm mercury. The Daguerreotype was displaced in 1851 by the new and cheaper wet plate collodion process, which permitted unlimited reproductions, and which prevailed until George Eastman perfected a dry out-plate process in 1879.

In his introduction to Pencil Sketches of Montana, Mathews expressed a bourgeois view on the aesthetics of outdoor photography:

The writer has frequently been asked why he did non have a Photographic Instrument along, in order to photograph Mountain scenery; for information technology is more often than not supposed that a photo of Mountain scenery is always perfectly accurate. This, however, is far from being the example. In taking a picture, the lens of an instrument must be adjusted to focus on a sure object or objects; and all others more distant, or nearer, volition be more than or less indistinct. Another disadvantage of an instrument is that objects most at paw are magnified, while those farther off are reduced in size. And then credible is this defect in large photographs of persons that a modest motion picture is now first taken, and afterward copied and enlarged. Shadows, too, are apt to be deepened and lights intensified. A good artist can, with ordinary care, produce a more accurate and pleasing picture with the pencil or brush.

Fundamentally, Mathews' objection is nevertheless valid. The human eye, linked to the encephalon, is of course subjective, and thus selective; the photographic camera lens, reacting only to light within the range of its own inanimate eye, is objective and comprehensive. However, during the twentieth century the medium became and so integral a part of everyday life, worldwide, that its optical illusions are now tacitly accepted every bit realities.

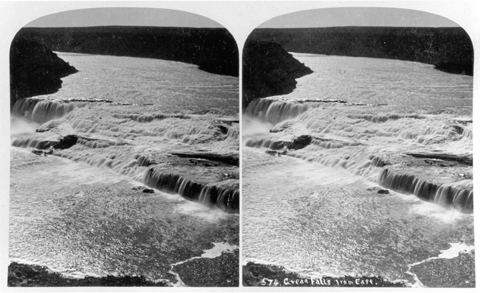

F. Jay Haynes' Stereo Photo

First Photograph

Past F. Jay Haynes

Haynes Foundation Collection, Montana Historical Society. H-327.

As far as nosotros know, Frank Jay Haynes was the showtime photographer to capture the Peachy Falls of the Missouri. Haynes shot this view with his twin-lens stereographic camera. A special hand-held stereo viewer, called a stereoscope, is necessary to meet the iii-D effect.

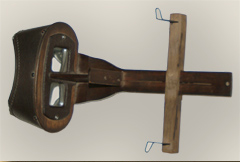

Stereoscope

Historical Museum at Fort Missoula

A stereoscope," explained Oliver Wendell Holmes, "is an instrument which makes surfaces wait solid. All pictures in which perspective and light and shade are properly managed, have more or less of the effect of solidity; but by this musical instrument that effect is so heightened as to produce an appearance of reality which cheats the senses with its seeming truth."[fn]Oliver Wendell Holmes, "The Stereoscope and the Stereograph," The Atlantic Monthly, three (June 1859), 738 .48.[/fn] The instrument was invented in England in 1838.

F. Jay Haynes

Montana Historical Society Archives.

Photographer F. Jay Haynes stands beside his stereographic camera at the "handsom Fall" in 1880. The shutter was a hinged device in front of the twin lenses, operated by manus. His portable darkroom is probably on a nearby wagon.

Although the huge herds of bison were absent, the rattlesnakes were still numerous, so Haynes prudently carries a six-shooter under his belt for self-defence.

On 12 July 1860 Captain William F. Raynolds and a five-human being detail from the Missouri River contingent, visited the falls of the Missouri, with Biddle's edition of Lewis and Clark's journals in paw. "Their description is remarkable for its vividness and accuracy," Raynolds found, "and as I passed downwardly I compared it signal by point with the scene before me, verifying information technology in every essential respect." Early the next morning time, the expedition's topographer and assistant artist, J. D. Hutton, set out with ii assistants to have a photograph of the Great Falls. He returned at nightfall, according to Raynolds, "having indifferently accomplished the object of his expedition."[fn]Due west. F. Raynolds, Report of the Exploration of the Yellowstone River (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1868), 109.[/fn] Since no such photo has nevertheless been found, we may assume information technology wasn't worth keeping.

Experiments that ultimately led to the invention of the camera equally we know it began early in the 1700s and steadily gained momentum through the opening decades of the nineteenth century. In 1816 the first successful attempt to combine the camera obscura—the instrument Lewis wished he had brought along—with photo-sensitive paper. By 1839 the Daguerreotype photographic camera, which captured images on chemically prepared copper plates, made photographic portraiture an important commercial enterprise.

Wet-plate technology, perfected in 1851, added impetus to the ever-widening popularity of photography as a documentary and artistic medium. [12] The George Eastman House Timeline of Photography, www.eastman.org/5_timeline/1849.htm (Link expired) A glass plate coated with light-sensitive collodion produced a negative image from which multiple paper positives could exist made.

The plate had to be exposed immediately afterwards the collodion was applied, and promptly stock-still with chemicals, which required a low-cal-proof darkroom. The technology was tiresome, undependable by today'southward standards, and the heavy equipment it required made an indoor studio the most practical operating venue. That may accept been the reason for J. D. Hutton's "indifferent" results. Only a good lensman with space patience, great physical endurance, a crew of dedicated helpers and a superior proficient luck, could venture far afield. Frank Jay Haynes was just such a person.

Meanwhile, in 1877, while wet-plate photography was still at the acme of its development, and stereography (3D photography), which had originated in 1841, was increasing in popularity, Haynes set upwards a studio at Fargo, in Dakota Territory. 3 years subsequently, he and a crew of vii administration set up out on a 1,200-mile picture-taking circuit up the Missouri River, photographing key points along the route, all the style to the falls. Their supplies and equipment, including a light-proof tent for a darkroom, filled 2 horse-drawn wagons.[fn] Untitled typescript page past Jack E. Haynes, son of F. Jay, in Vertical File "Frank Jay Haynes," Montana Historical Lodge, Helena.[/fn] "This trip," he wrote to his wife, Libby, "is going to be worth a fortune to me for it is going to open up a new field."[fn]Edward W. Nolan, Northern Pacific Views: The Railroad Photography of F. Jay Haynes, 1876-1905 (Helena: Montana Historical Society, 1983), p. 38. In 1881 Haynes became the official photographer for the Northern Pacific Railroad, and soon became famous for his pop stereographs of scenes in Yellowstone National Park. In the mid-eighties he switched to George Eastman'south revolutionary new dry-plate process.[/fn] Haynes returned to Fargo late that summertime with historic photos of both the "beautiful cascade," otherwise known as "handsom autumn," and that "sublimely k object," the Great Falls of the Missouri. At long final the world could share Meriwether Lewis's "pleasure and astonishment"—in stereovision!

"Sublimely grand specticle"

Great Falls of the Missouri River, Yard.T.

Photographed by F. Jay Haynes, Summertime, 1880

Montana Historical Society H-326, Haynes Foundation Drove

This is one of the earliest existing photographs of the Great Falls, taken from the bespeak at the edge of the high prairie where Lewis may have made his hard descent for his closeup study of the scene.

F. Jay Haynes (1853-1921) was an important early on photographer of Western scenes and people. He shot this photo merely a few months before a pioneer settler and entrepreneur named Paris Gibson rode his horse from Fort Benton, forty miles downriver, to run into the sight he had read of in a reprint of Nicholas Biddle'south edition (1814) of the Journals of Lewis and Clark. He was inspired by the potential for industrial development of the falls, and envisioned a twenty-four hours when "water power could exist shipped across the state past ways of electricity." 2 years after Gibson founded the city of Slap-up Falls, Montana, a few miles upstream virtually Black Eagle Falls, the last of the v cataracts Lewis discovered. Within some other decade Peachy Falls gained the nickname "The Electrical City."

1888 Century Illustrated

"Great Falls of the Missouri" [thirteen] Eugene Five. Smalley, "The Upper Missouri and the Great Falls," The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, Vol. 35 (New Series thirteen), No. 3 (January 1888), 415.

Mansfield Library, The University of Montana, Missoula.

Idue north the fall of 1888 the Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, i of the leading literary magazines of the second one-half of the 19th century, sent a writer and an artist out due west to make a trip down the Missouri from Helena, Montana, to the falls and Fort Benton. Equally a guidebook they apparently carried a reprint of Nicholas Biddle'due south paraphrase of the Lewis and Clark journals. [14] Fewer than 1,500 copies of the original Biddle-Allen 1814 edition of the journals were printed. However, Harper and Brothers, of New York, republished the Dublin 1817 edition of Biddle'southward … Keep reading

Viewing the Great Fall from the heights on the south side, the writer observed:

We could only meet the entire latitude of the autumn from a unmarried point on the farthermost verge of a crag jutting over the cañon. There was no way of getting downward into the gorge to the water'southward border, which is most four hundred anxiety below the general level of the country. The deep crease in which the river runs is entirely lost to view a quarter of a mile abroad. Its lips seem to close upwards, and appear like the many modulations in the grassy plain, so that a traveler riding across state might come about to the sheer verge of the cañon earlier he would suspect that he was approaching one of the great rivers of the world.

Wheeler's Centennial View

Olin Wheeler (1852-1925) was the first author to produce any pregnant works most the Lewis and Clark expedition. His major contribution to the literature was The Trail of Lewis and Clark, 1804-1904; with a description of the old trail, based upon actual travel over it, and of the changes found a century later [15] (2 vols., New York: One thousand. P. Putnam's Sons, 1904). Wheeler'south importance in the historiography of the trek is briefly discussed in Paul Russell Cutright, A History of the Lewis and … Continue reading . Actualization in 1904, just eleven years afterward Elliot Coues's meticulously annotated reprint of Biddle's paraphrase, and a year before Reuben Aureate Thwaites' similarly thorough transcription of all the original journals and so known to exist, Wheeler's book brought to a wider public his personal impressions of the story of the trek, the waters they navigated and the country they traversed. Among the 2 hundred illustrations information technology contained were numerous views of important expedition scenes and landmarks photographed past the various professional lensmen who accompanied him in his retracings of the route. (See Wheeler's "Trail of Lewis and Clark".)

Unfortunately, the identities of only a few of those photographers are known, including L. A. Huffman of Miles City, Montana, who was a protégé of F. Jay Haynes. A few images are in the Edward Ayer Collection at the Newberry Library in Chicago, only an intensive search for original prints or negatives of the remaining photos included in The Trail has been fruitless.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Mean solar day past Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Printing, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) past Gary Due east. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.

0 Response to "Scientist on the Trail: Travel Letters of a. F. Bandelier 1880-1881"

Post a Comment